An interview with Bill Tempero

Tempero drove this Longhorn/Chevy during the month of May in 1983. After surviving a spin in Turn 2 on May 20, he made a qualification attempt the next day, but was waved off after one lap. Photo credit: IMS Photo Archive

The Gist

Bill Tempero, the former CART and Can-Am racer who founded the American IndyCar Series, reflects on his racing career and shares some fascinating stories on and off the track, in this exclusive interview with Champweb.

Bill Tempero once told a journalist, “I think that it’s unbelievable that an average guy like me can just come up and compete with the best in the world.” That was in 1974, when Tempero was still making a living as the owner and operator of a gas station in Fort Collins, Colorado. And yet, he was already a familiar name at the top of the rankings in the American amateur road racing scene. Multiple times an SCCA Midwest division champion during the 1970s, Tempero soon found himself racing against the likes of Mario Andretti and David Hobbs in Formula 5000, a series that looked very much like Formula 1, but featuring production-based American V8 engines.

From the start, Tempero worked on his own race cars, fielded his own team, and raced on a limited budget, and he would carry this “do-it-yourself” ethos throughout his career. Tempero gravitated towards road racing instead of the more lucrative oval racing, at one point even considering a career in Europe to go for Formula 1. Sponsorship eluded him despite multiple victories in the junior categories, but nonetheless he was able to race at America’s finest tracks in Formula 5000, Can-Am, and CART. He also practiced an Indy car at the famed Speedway, too, although he never qualified for the 500.

During the late-1980s and 1990s, Tempero was perhaps best known for founding and racing in the American IndyCar Series, and for fielding one of the first teams in the upstart Indy Racing League. Now retired from racing and currently serving as the President of the United States Cavalry Association, Tempero kindly took the time to reflect on his Indy car racing career and the series that he founded.

Bill Tempero did all the work on the stock-block 355 Chevy motor in this Wood Power Systems/Spirit of Colorado Eagle. Tempero attempted to qualify for the 1980 Indianapolis 500 but did not complete his qualifying run. Photo credit: IMS Photo Archive

Bill Tempero

"You could afford our series like running a late model car, for $50,000 to $100,000. To race in CART or IRL, you're probably looking at a minimum of $3 to 5 million."

SKC: You’d always carved your own way through the different road racing categories in America. What was it like, being one of the few drivers who went with the stock blocks in CART?

BT: It was a whole different time in history. When I started racing IndyCar in 1980, you could build your own engine and be halfway competitive. A few of us were running stock block engines: Dan Gurney was running one, I was running one, Jet Engineering from Michigan - there were 4 or 5 cars running stock blocks. At Milwaukee, Mike Mosley drove for Gurney and he started last and won the race in a stock block. It was phenomenal. In my case, I was building my own motors and everything. A guy could build a stock block in those days for $25,000, and a Cosworth would cost, maybe $60,000 to $75,000.

SKC: As the Cosworth became ubiquitous by the mid-eighties, it must have become difficult for the stock block competitors to keep up.

BT: The problem was, we just weren't spending that kind of money. [The other car owners] had decided that they wanted to spend money [on purpose-built turbo Cosworth and Chevy engines], and guys like me just didn't have that kind of money.

When that happened, I thought, there's got to be a place for us guys with stock blocks. I was racing in the Can-Am series around 1985-1986. We had the Indy cars that we put fenders on, to run in this series. Then the SCCA said they wanted to kill the series, and now we had to use the name Can-Am Teams in 1987. After that, I started the AIS in 1988 and took the fenders off!

Bill Tempero during his last Indy 500 attempt in May 1983. Photo credit: IMS Photo Archive

SKC: There was a variety of older, cheaper Indy cars competing in the series. How did these cars generally find their way into the AIS?

BT: When you needed a new car every two years in CART or IRL, there were enough available cars sitting in somebody's shop that you could buy at a reasonable price. The AIS was an outlet for somebody to get rid of their cars. The car I had for Buddy Lazier was an ‘85 March - it was the Budweiser car from Jim Trueman. I had bought two of the cars from him and put stock blocks in them. Usually I would convert the cars myself [to fit a stock block engine] and sell those for people to use, so they wouldn't have to convert the cars themselves.

The hard part is that you've got all these cars that are 4-5 years old. So I put all these rules together and let all these cars compete. The first couple years we used only 355 cubic inch stock blocks, and then all of a sudden the turbo Buicks were available, because they finally outlawed them in CART. So now I let the turbo Buicks in, and that increased the Chevrolets to 377 cubic inches, so that the steel blocks and aluminum blocks could compete with the Buicks. I tried to balance all that out, and it worked pretty well, it really did.

I wasn't trying to make a “cheaper” series, I was trying to make it affordable for guys who thought they had a talent, to find out if they really had the talent. You could afford our series like running a late model car, for $50,000 to $100,000. To race in CART or IRL, you're probably looking at a minimum of $3 to 5 million.

Bill Tempero at an AIS race in 1988 at Mountain View Motorsports Park in Mead, Colorado. Photo credit: Joe Starr

SKC: You ran and competed in the AIS between 1988 and 1999, right?

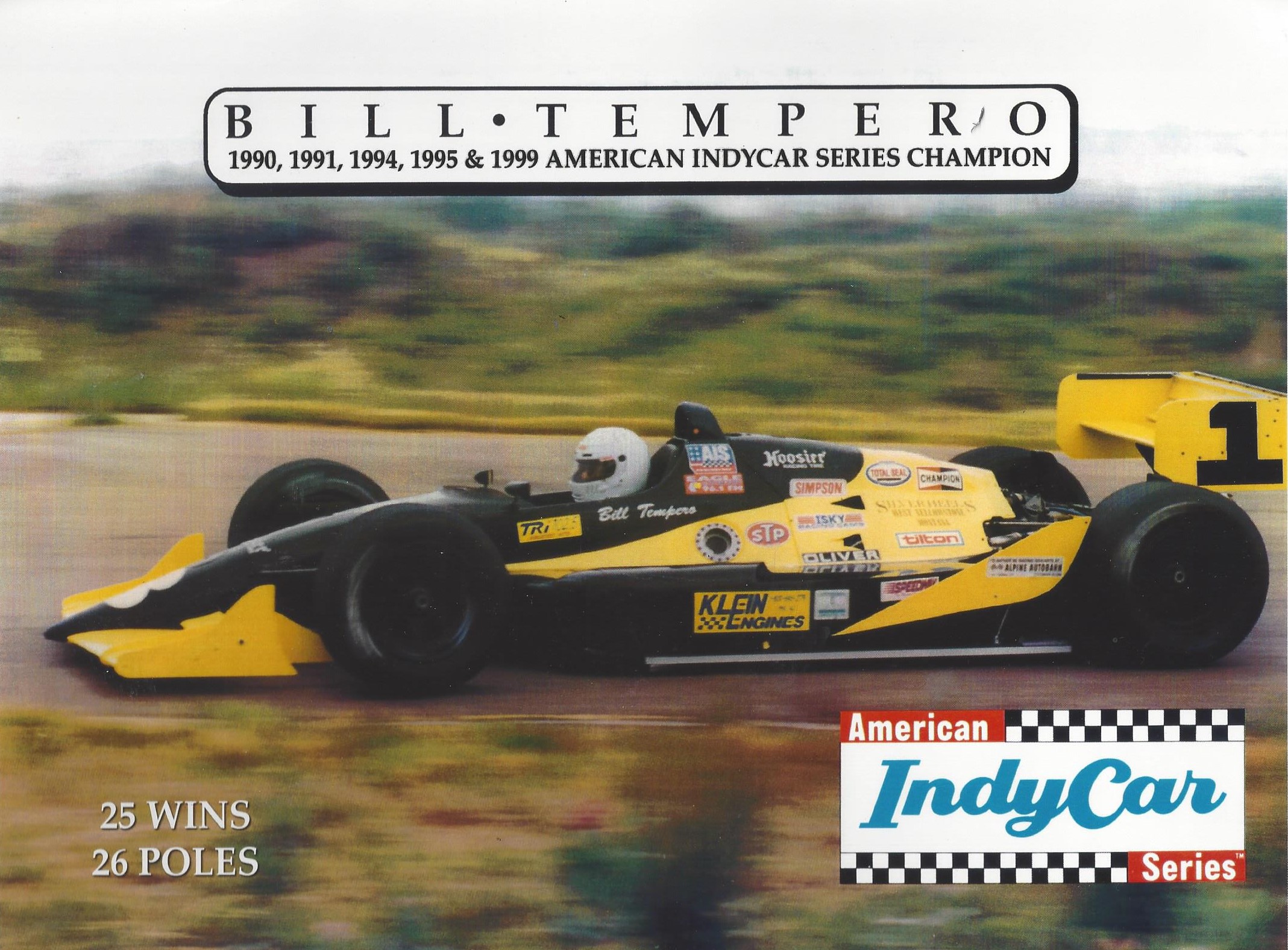

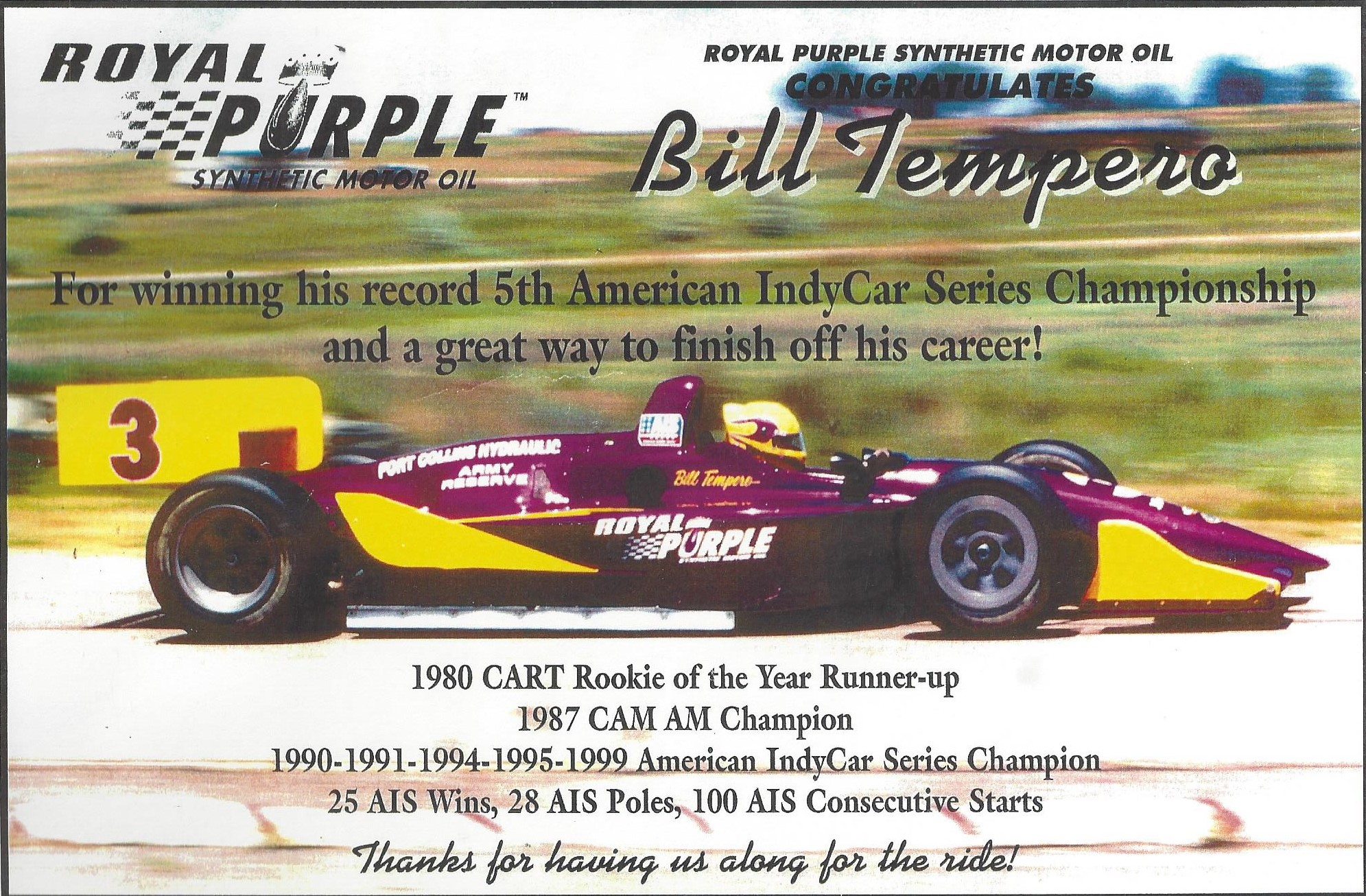

BT: We did exactly a hundred AIS races. I did a hundred consecutive races, won 25 races, had 26 poles, and I won five championships. During the last year, I had sold the series, and [the new owners] paid me to run the series. They had really good intentions and just didn't work out. I was only committed for one year [as the manager of the series] and then I don't think it went any farther than that. The last race I drove was the 1999 Los Angeles Grand Prix, which I won!

SKC: What were some of the more memorable races that you put together?

BT: We went to Puerto Rico for a street race, and that was a pretty good challenge. We also did a street race in Ensenada, Mexico, another one in Monterrey, Mexico, and one in Juarez. Street races are hard to put on - it's a lot of work! We also had a race at the parking lot at the Reno Hilton - that was a pretty good accomplishment. Basically, I was a one-man band putting on a street race. I didn't have any help - I got help when I got there, but I was the one doing it by myself.

We also did a street race in Halifax, Nova Scotia. In fact, we did three of them. [The 1990 race] was a good race between Johnny [Unser] and myself. We were running 1-2, and on the last lap he clipped the wall and I won the race. That was not supposed to happen, but it did!

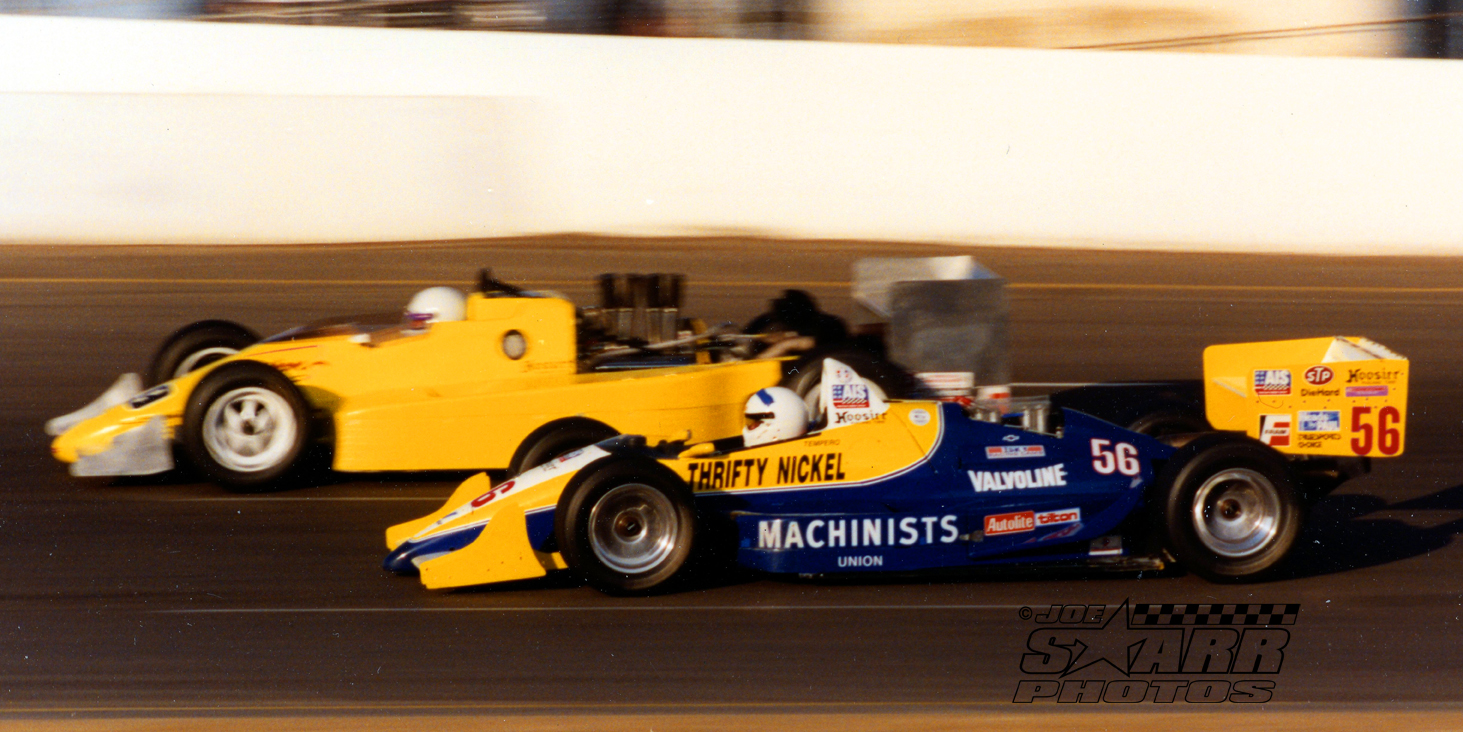

The future Indy 500 winner Buddy Lazier leads Bill Tempero at an AIS race at the Colorado National Speedway. Photo credit: Joe Starr

SKC: You mention that street races are hard to put on. What were some of the challenges you faced when organizing the AIS races?

BT: Put it this way - I found out that race car drivers have egos, or they wouldn't be doing it. Then I found out that car owners have bigger egos. And then I found out that race track owners have even bigger egos! I put on a hundred races, and I could write a book on each race!

Dealing with the track owners, dealing with cities and city mayors, it's just a phenomenal amount of work to put all the pieces together. With the street races - welding the manholes, filling the potholes, where do you want the portajohns and how many do you want? And bringing in seven officials, flying them in. It just goes on and on, a big production. But we got it done, we did a hundred races! And the fun I got out of that was driving the car, even though sometimes I was worn out and I couldn't drive the car. But as I say, no complaints.

SKC: Unfortunately, the AIS did not have much television and media coverage. Do you think there could’ve been more attention to the series?

BT: I was probably so consumed with getting everything else done, and I didn't have the finances to hire a PR person. It was so consuming just to put on these races and guarantee a decent purse and tow money. It’s okay - I did what was humanly possible to accomplish and I feel good about what I accomplished.

Robby Unser leads Bill Tempero at an AIS race at the Colorado National Speedway. Photo credit: Joe Starr

SKC: Did the series consider racing on the big ovals? At one point, Pocono was on the schedule but there was no record of the series having raced there.

BT: We sure stayed off the big ovals! We couldn't afford to tear up equipment. Coming back from Halifax one year, we stopped and tested at Pocono for a day. When we were done, I said, “We're never running a big oval.” They wanted us to have a race there, but I said, “If you want to destroy the series, that's how to do it.” CART stopped racing there, too, didn't they? Instead of a safety wall, the walls were steel boiler plate, it wasn't even a cement wall! We don't need to lose four or five guys and we don't need to hurt anybody. I always said after each race: what made this a successful race was that nobody got hurt. [In the history of the AIS], somebody might've broken an ankle, but nobody got [seriously] hurt.

SKC: Let’s talk about the personalities of the AIS. The series featured drivers from all walks of life and ages. How did they all get along?

BT: It was a really good atmosphere. We had more young guys than we had older guys, and the young guys were trying to make it in the world of Indy car racing. They were very competitive and very ambitious. It was tough, and no different than the young guys who are in it today. I might've been the oldest driver - we had a few in their 30s and 40s, but also younger drivers like the Laziers.

CART and IRL didn’t have such a friendly atmosphere - it was “whatever it takes to beat your opponent.” In AIS, I kept telling everybody, you beat them on the track, but don't beat them in the pits. You help them, everybody helps everybody get to the grid. I preached and preached that philosophy, and it worked. In CART and IRL, you were an island, whether you were a little guy or Penske or whoever.

The AIS featured Indy car chassis converted to fit larger stock block engines. Tempero is seen here driving an ‘88 March at an AIS event in 1990. Photo credit: Joe Starr

SKC: How did you feel to see your 1988 AIS champion, Buddy Lazier, win the Indy 500?

BT: It was great! I know he appreciated the AIS very much. In fact, he told me that a few times. We had some very good, very hard races with him and Robby [Unser]. Buddy had never been in an Indy car before he came to our series. We ran him out of my shop - his dad, Bob Lazier, was a good friend of mine. So I took care of Buddy and ran him in one of my cars, and then I ran [his brother] Jaques for one year. And the two Unsers were running with us for a while.

SKC: What was your impression of Robby Unser? He was the 1989 champion and had an impressive string of victories that season.

BT: Robby was a good driver, too. I don't know if he put his heart and soul into it, but he had raw talent. Bobby [Unser] was a good friend, Robby was his son and Bobby would come to all the races. I also had Rodger Ward as our chief steward, but I didn't know there was a conflict between Rodger Ward and Bobby Unser. I found that out later!

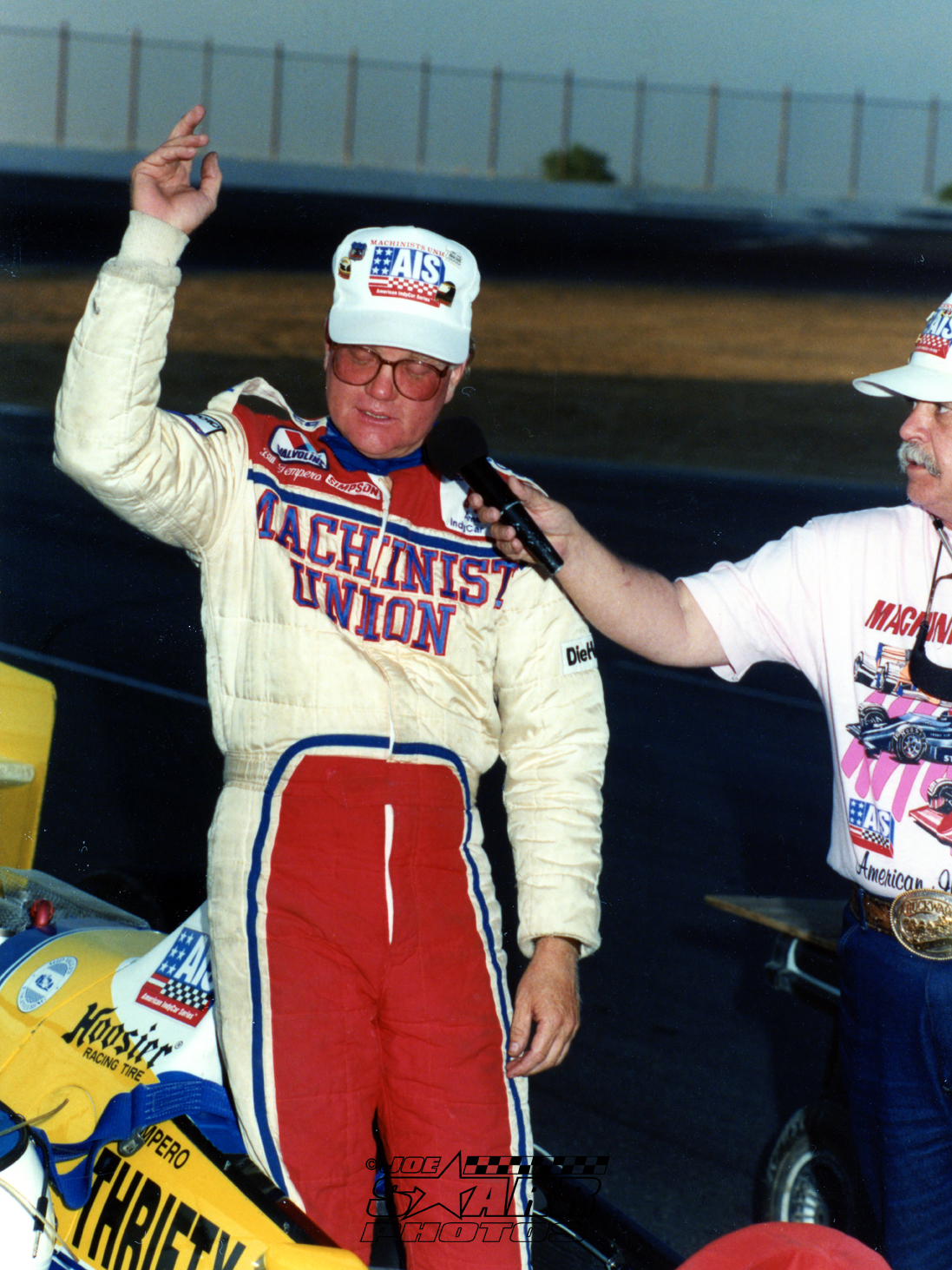

The Machinists Union sponsored Bill Tempero’s team and was also the title sponsor of the series. Here, Tempero addresses the crowd in Colorado during an AIS event in 1990. Photo credit: Joe Starr

SKC: Who else comes to mind as stand out talents in the AIS?

BT: I'm sorry that Greg Gorden didn't continue in IndyCar. Kevin Whitesides also had the talent to make it. Robby could've been a champion in CART or IRL. Johnny could've been. Buddy was a champion! Jaques Lazier could’ve been champion if he’d stayed with it.

SKC: You raced in CART for several seasons before rejoining Can-Am and founding the AIS. Tell us more about your experience in CART.

BT: When I was racing in CART, I had to pick and choose [where I raced] to make it affordable, and the prize money meant so much to keep us going. I didn’t get rich and famous in CART, but we had some good runs. I finished 6th at Milwaukee and 8th at Cleveland, against all the turbos, so I felt good about that. I was doing my own motor, engineering, aerodynamics, and setting the car up. But I couldn't afford to keep going to every race.

Pat Patrick was a good friend - he and Penske were running CART. I wrecked a car at Milwaukee one year and was sitting on the wall, and Pat said, “Are you going to make the race in two weeks at Atlanta?” I said, “I'm out. I don't have money to fix the car.” He said, “How much do you need?” I looked at the car, and I said I needed ten grand. He wrote me a check for ten grand, and then he took it out of my purse at every race until he was paid back! A thousand out of each race. But I made the race!

There were some good people in CART, but not very many. Pat Patrick was one of the good people in CART that I got to know. [Another was] Andy Kenopensky, who ran the Machinists Union cars. He was a really princely guy. Back in my first year at Indy, we didn't have much money. He said, “How are you doing, Bill?” And I said, “Well, it’s hard to put everybody up in the motel rooms.” And he said, “Why don’t you stay with me and I’ll pay for your room?” And he did that.

While Tempero has never served in the armed forces, he proudly carried the US Army Reserve on his car and helped raise money for military families as a way to give back to the community, Photo credit: Joe Starr

SKC: Fast forward to 1996. You were already eight years into the AIS and over a decade since your last CART race, but now you had an opportunity to race in the IRL. Tell me about that season.

BT: I was trying to race in the IRL at the same time as the AIS - that was a tough thing - trying to run two cars [in each series]. I hadn't been on a big oval since 1983. I had just done short ovals and road courses. For our first race we went down to practice at Orlando, a one-mile oval. It was a month before the race when they had open practice. I wasn't very comfortable, so I went from there to Phoenix by myself, and practiced some more. And I called my wife and said, “I'm not liking this. I'm going to stick to short ovals and road courses.” So when we did a few IRL races, I put another driver in the car - Dave Kudrave, a good driver and good person - and JC Carbonell, who had a lot of talent but didn't get it all put together. At the time, I was still having fun on the road courses and short ovals. My background is road racing, you know. And it was too much to do both - I couldn't do both.

SKC: You drove a lot of different Indy cars over the years. Which one is your favorite?

BT: That would be the ‘96 Lola. It still had some good ground effects and sequential shifting. It was a really, really good car. I did a commercial for Juan Montoya - he was driving the Target car for Chip Ganassi. We took our car and made it look like a Target car. We took it to Sebring, and at that point I was running it with the turbo Buick. Montoya did a few shots with us, and then I did. When we were all done, he asked, “Is it okay if I drive as hard as I can in this car?” I let him do four or five laps, and afterwards he told me, “This is one of the best cars I ever drove.” So that’s when I knew that it was a good car.

We did another commercial with Juan again, but he was only there for one day. He said, “I don't want to hang around, here's my suit and helmet, you do the commercial!” I shouldn't have sent the helmet and suit back to him!

Bill Tempero wins the Rocky Mountain IndyCar 150 at the Colorado National Speedway in 1991. Photo credit: Joe Starr

SKC: Do you still follow IndyCar and what do you think of the series today?

BT: Absolutely, but I think they better be careful, they're going too fast on some of the ovals like Texas. I don't care if you're driving a tank at 250 mph but if you hit something, you'll get hurt. An IndyCar driver doesn't want to die for the sport. He's out there to be the best and to make a living at it, but he doesn’t want to die. That's not what he's out there for.

The safety walls at Indy have made a big difference to everything, but I still think open wheel at Texas is pretty dangerous. It’s a pretty simple deal - you either cut the boost down or put a bigger wing on it. It doesn't cost anything to do that - run a road course wing at Texas, and you'll run 25 mph slower and the racing would be fantastic!

SKC: What’s your favorite racing story that you’d like to share?

BT: We’re running at Sanair as part of the Can-Am Teams series in 1987. They had brought in a local hero, Jacques Villeneuve Sr. [brother of Gilles], to run in our race. And we’re just about the same speed, he was a little faster in practice. But lo and behold, I got the pole, Jacques was second and we were both a half second ahead of everybody else in the field.

So I went over to him, and I said, “Jacques, do you want to make a good show out of this for your hometown?” Jacques said, “What do you have in mind?” So I said, “It's a 60-lap race. Every 10 laps if we're together, let's switch the lead. But the last 10 laps the bets are off, okay?”

So he agreed to this! I started on the pole, but he jumped the start and took off. I thought, you asshole, you're not going to play the game. After 10 laps, I'll be damned, he lets me by! So that's pretty cool. We did it back and forth, up to 50 laps and the bets are off. Jacques smoked his rear tires, and I thought he's going to take the wall out. I pushed right up to him, he got it sideways and I got by him and won the race! He wouldn't even come to the podium. So here I am looking at my French trophy in French! It was fun, a good story, and I never talked to him again!

Bill Tempero in one of his Lola Indy cars during the mid-1990s. Image credit: American IndyCar Series

SKC: Do you think there is a place for a series like the AIS today?

BT: No, not at all, because of the economics. When the AIS was formed, there were a lot of guys who wanted to get to Indy. Now, a lot of guys want to get to NASCAR. The few guys that want to get to Indy, they [already] got the feeders - the Indy Pro series and Indy Lights - so that's where they're going. When the AIS was formed, there were twenty guys like me! When I started racing in SCCA Formula Ford and Formula Vee, there were 50 guys who wanted to get into that. I remember being at the June sprints at Elkhart Lake, and there were 101 Formula Ford cars on the grid! It was just a whole different [time], and there were just so many people who wanted to get to Indy. The AIS filled that void and helped fulfill the dream for some of them.

SKC: How would you sum up the American IndyCar Series?

BT: It was a good chance for people that didn't have a million dollars to find out if they had the talent or not, and a few drivers found out they did have the talent. And when they found out, they pursued their dream and their dream came true. If the AIS hadn't been there, they may not have had the chance to see if they really had what it took.

I was very proud of the series, but it was physically and mentally a killer! I don't want to think about doing it again! But it's okay, everything is cool. I met a lot of good people and we had a lot of good people in the AIS.

Bill Tempero’s favorite Indy car, the Lola T96/00. Image credit: Unknown

SKC: After you retired from racing, you focused your attention on the history of the United States Cavalry, in fact, joining and becoming the president of the US Cavalry Association. How did you become interested in the calvary?

BT: I grew up on a farm, about 20 miles from Fort Riley. My dad had a veterinary practice and we had horses. And when the cavalry disbanded, they were selling all the equipment, and my first saddle was a cavalry saddle. I guess the seed was planted then. But I always had the history bug, so when I retired from racing, I could put all my efforts towards that. I had to switch gears from 1,000 horsepower to one horsepower! And I found out there’s more to life than racing. There truly is.

SKC: Not many people today might appreciate what the calvary was. Can you share with us how it played an important role in American history?

BT: Before we had mechanized units, all we had were foot soldiers and cavalry. We’ve lost 1.2 million men and women who served and died for our country. 980,000 horses died serving our country.

When students go to West Point, the first thing they teach is military history. And there’s a reason for it. We have to learn from our mistakes and we can’t forget where we came from. And that’s also the mission of the US Cavalry Association. Last week, we had 200 school kids [at the National Cavalry Competition] and we got to talk to them, they got to watch the competition, and that was cool!

Col. Bill Tempero (left) at the 2022 National Cavalry Competition. During the weeklong event, competitors demonstrate their proficiency in horsemanship, jumping, mounted saber and mounted pistol drills. (Photo credit: United States Cavalry Association)

SKC: I understand you’ve done some other work to support the men and women of our military for a long time. Please tell us about that.

BT: I never served, but we’ve been involved in the military for over 30 years. My wife and I started, about 30 years ago, raising money for military families through a military family hardship fund. People don’t realize, when someone from the National Guard or Army Reserve is called up, they might be in their 40s, with families, kids in college, house and car payments, and making hardly any money if they’re [deployed] for two years. Some of the families really have a hard time, so we’ve been raising money for them through the fund, and we still do.

Because of our work, the military gave me an honorary colonel’s commission and an official letter signed by the head of the Army. When they gave that to me, a hundred soldiers stood up and saluted me. It was the best day of my life!

Like this type of content? Want more?

Submit your email address below so we can email it to you.