Mike Lee: the Unknown Indy Car Champion

The Gist

Mike Lee was an aspiring racer who had a dream to race Indy cars. In this exclusive interview with Champweb, he discusses how the American IndyCar Series gave him that opportunity and shares some insight into the world of second-hand Indy car racing.

Beneath the blue New Mexico sky on the outskirts of Albuquerque, Mike Lee is shooting a scene at an old gas station for a documentary series called “Legends of Route 66.” Decked out in a cowboy hat and Western outfit, this storyteller of roadside Americana might not be your idea of a racing driver, let alone an Indy car champion.

But in fact Lee holds the very same Indy car title that once launched Buddy Lazier on the road to IndyCar stardom. In 1988, Lazier was the first driver to win the American IndyCar Series championship. Lee was the last driver to do so in 2000, before the series went defunct.

Chances are, you’ve never heard Lee’s name next to the Unsers, the Andrettis or even Lazier, who went on to win the Indianapolis 500 and the Indy Racing League championship. That’s because the American IndyCar Series, or AIS, was often dismissed as a minor league series that raced in smaller markets, and rarely got any media coverage beyond the local papers.

“I have witnessed a lot of bashing on social media of the AIS by so-called experts,” lamented Lee. “We didn't always have the best equipment, safest tracks or ‘big name’ drivers. But we raced our asses off and had the time of our lives.”

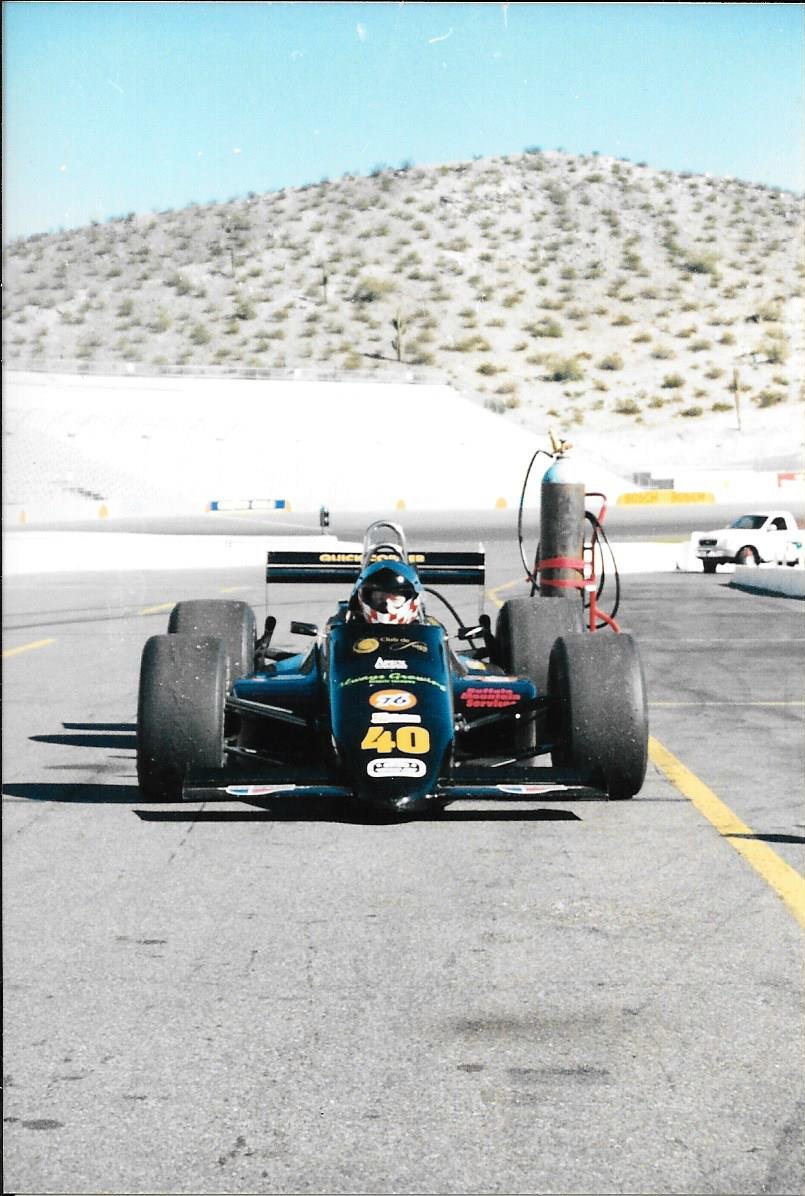

Mike Lee at Sandia Speedway in New Mexico. This is one of two 1990 Lolas that Lee would race during his stint in the USSS, which was the successor to the AIS. (Photo: Mike Lee)

Mike Lee

"None of us were there for fame and fortune. We were there because we loved it."

So what was the AIS all about? Even in relative obscurity, the series featured serious machinery: many of the cars were Lola and March chassis that had previously raced in CART and the Indy 500, with stock-block engines ranging from a 5.9L Chevy V8 to a turbocharged 3.4L Buick V6. Not to be confused with vintage racing events where priceless racing cars are driven well below their limits, the AIS Indy cars were raced in anger, reportedly topping 200 mph on certain straightaways.

“Many competitors ran Buick turbos with no pop off valves like they had in the past,” Lee recalls. “There were no limits on turbo boost, so we put a plate over the pop off valve port. The result was unbelievable horsepower.” Lee himself drove two March 86Cs (one of them formerly driven by Rocky Moran), an ex-Dominic Dobson Lola T90/00, an ex-Galles Lola T90/00, an ex-Newman-Haas Lola T93/00, as well as an upgraded March 86A Indy Lights car, all of these configured to fit a Buick V6 engine.

Mike Lee was an aspiring racer in the Barber Dodge Pro Series during the 1990s. (Photo: Mike Lee)

How did Lee come to drive these untamed championship cars? The story begins in the 1970s in Rochester, New York, where Lee grew up. As a kid, Lee first heard the Indy 500 broadcast on the radio and quickly became interested in the sport. “The deal was sealed when my dad took me to the 1977 Indy 500,” Lee remembers. Soon after watching A.J. Foyt’s record-breaking fourth win, Lee raced snowmobiles in the WSRF and ESRA ice oval series, and moved onto stock cars at local tracks during the 1980s.

Still in pursuit of his dream of being an Indy car racer, Lee entered the Fastrack Driver Search in 1990 and tested a March 87C Indy car as part of the program. Lee soon realized he needed more experience in smaller formula cars before racing Indy cars. During the 1990s, Lee attended the Bertil Roos driving school at Pocono, ran some sports cars, Formula Continental, as well as the Barber Saab and Barber Dodge Pro Series before landing a deal to be a test driver “for an up-and-coming F2000 manufacturer.” By 1998, Lee felt ready to race with more horsepower and put together the funding to race in the AIS.

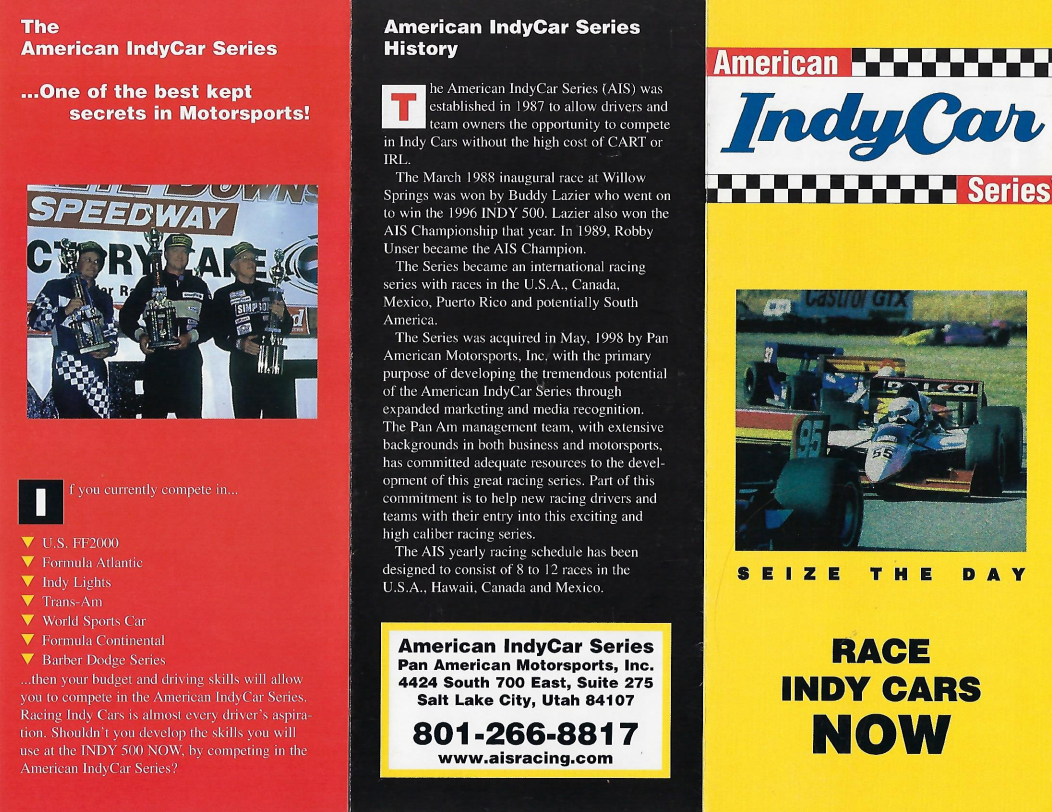

Brochure explaining the American IndyCar Series to prospective competitors, likely from the last couple years of the series before it went defunct after the 2000 season. (Mike Lee collection)

The affordable path to go Indy racing

The AIS was created in 1988 by ex-CART driver Bill Tempero, who had most recently been competing in Can-Am with a modified March Indy car. Conceived at the same time as CART was moving towards expensive, manufacturer-backed turbocharged engines, the AIS offered a way for teams to go Indy car racing at a fraction of the cost of a CART season, using older chassis and cheaper engines. The schedule included a variety of circuit types, from street and road courses to half-mile ovals.

In its early years, the series enjoyed an association with two-time Indy 500 winner Rodger Ward, who served as Chief Steward, and Bobby Unser, whose son Robby raced in the series. It even attracted title sponsorship from Machinists Union, which was also an entrant in CART. Among those covering the fledgling series was the respected motorsport magazine On Track.

From its inception, the AIS was composed of a mix of drivers of all ages and career paths. Some drivers eventually graduated to the top-level IndyCar series, including Buddy Lazier, Jaques Lazier, Robby Unser, Johnny Unser, Nicola Marozzo and Racin Gardner. During the early 1990s, the series even got “Uncle Jacques” Villeneuve (brother of Gilles) to enter a street race in Halifax, Nova Scotia. At the other end of the spectrum, the AIS featured “gentlemen racers” such as the businessman and adventurer Steve Fossett, who would later fly around the world in the Virgin Atlantic GlobalFlyer.

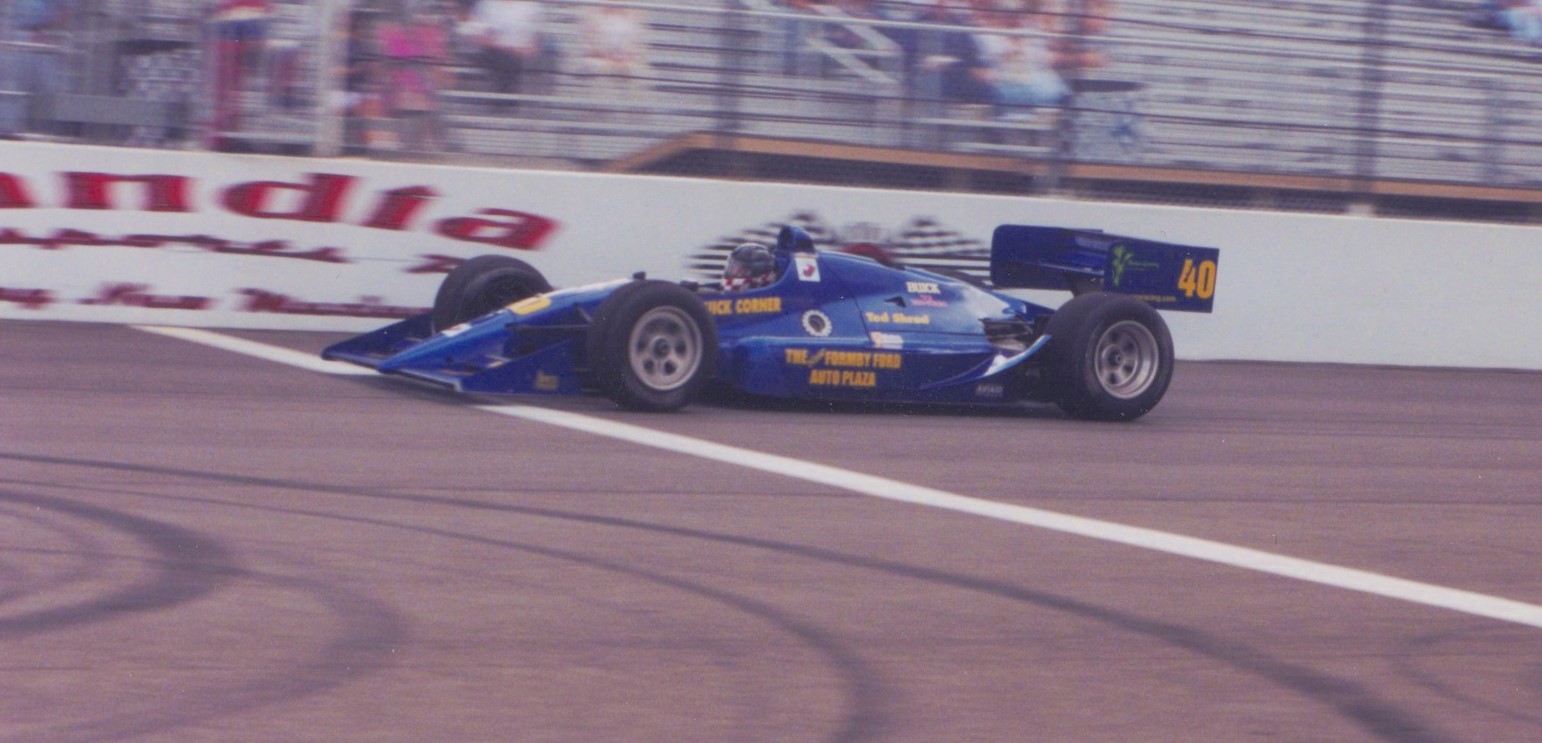

Mike Lee raced this March 86A during the 2000 season. By the late-90s, the American IndyCar Series allowed Indy Lights chassis to race alongside regular Indy cars. To ensure competitiveness, Lee’s car was fitted with a 600-horsepower Buick V6 and various other upgrades to the suspension, brakes and tires. (Photo: Mike Lee)

After a few years of declining media attention, the AIS had its moment in the spotlight in 1996 when several of its teams jumped at the opportunity to join the upstart Indy Racing League with their older equipment. Unfortunately, the AIS entries became a punchline in articles slamming the lack of quality of the entries to the inaugural IRL race at Walt Disney World Speedway. Of all the AIS-affiliated entrants that year, only Tempero’s team managed to take their cars to the green flag, utilizing the services of ex-CART racer David Kudrave and former Indy Lights racer J.C. Carbonell.

After Tempero left the IRL and returned to the AIS, he continued to position the AIS as a cost-effective road to the IRL. After all, the IRL did not have its own feeder series yet, and the stock-block engines favored by the IRL would not have been hugely different from the ones used in the AIS. Demonstrating this point, Jaques Lazier (younger brother of Buddy) and AIS team owner Joe Truscelli successfully moved from the AIS to the IRL in 1999, with Lazier eventually becoming a race winner. The 1998 AIS champion Greg Gorden also passed the IRL rookie test at Pikes Peak; however, he did not start an IRL race and continued to race in the AIS.

Championship… and controversy

Mike Lee also hoped to utilize the AIS as a stepping stone to the Indy 500, and joined the series in 1999. In only his second season in the AIS, Lee became champion after scoring consistent Top 5 finishes in a schedule that featured races at the Hallett Motor Racing Circuit in Oklahoma, St. Johns Airpark in Arizona, Pueblo Motorsports Park in Colorado, Sears Point in California, and Phoenix International Raceway in Arizona.

It was not without drama during the last race at Phoenix. Lee had come into the weekend with a slim points lead over J.C. Carbonell, a one-time IRL starter who was driving for Bill Tempero’s frontrunning AIS team. Lee said, “We arrived knowing we had to have a really good weekend to clinch the title.”

Saturday morning opened with the news that Carbonell was not at the track, having had his flight delayed from Chile. Practice and qualifying came and went as Carbonell’s car sat empty in the paddock. On race morning, Tempero reported that Carbonell was still expected to arrive before the race and that he would start at the back of the grid. But Carbonell never showed up, and his car was moved back into the hauler an hour before the race.

As Lee recalled, another driver further down the standings realized he now had an outside possibility of winning the championship from Lee. Employing a tactic more often seen in the cutthroat world of Formula 1, this competitor (who shall remain unnamed) lodged a verbal protest over the legality of Lee’s car. Lee remains adamant that there was no merit to those allegations: “He said our car was underweight. Which is hilarious because he outqualified me. The reality was that cars were never weighed in the AIS. You ‘run what you brung,’ and there was no weight rule in 2000.”

Nonetheless, Lee was wary of his rival making further complaints about his car, and made the strategic decision to handicap his own car before the race. “My crew chief took the seat insert out and attached steel barbell weights to the tub under and behind the seat. We weren't going to let [the other driver] play his games, and we knew if he didn't catch us on the track he was going to start whining. I ran the whole race with a car that was very obviously way overweight. It handled and braked like absolute garbage. We decided where I needed to finish to clinch the championship and I raced for 5th place as my goal.”

After what he described as a “hairy” race, Lee finished 5th and clinched the championship. But the controversy wasn’t over yet. As Lee recalled, his rival immediately protested the result to the series management. After some deliberation, the result was upheld and Lee was confirmed as the winner of the championship. Lee said, “No matter what, we won the 2000 AIS championship and had one hell of a party in Phoenix that night.” In a bit of an anticlimax, the series awarded Lee nothing more than a letter confirming his title. Happily, fellow racer Phil Erickson would later commission and pay for a “really nice trophy,” and several other drivers joined together to present it to Lee the following April.

An open-wheel split… again?

Despite the AIS title, an Indy 500 ride remained elusive, and Lee’s own racing career became wrapped up in politics surrounding the AIS after the 2000 season.

In 1998, series founder Bill Tempero had sold the series to an entity called Pan-American Motorsports. Under new ownership, the series had plans to grow operations and expand into the South American market, but some of the team owners disagreed with the new management and considered breaking away to a new series following the 2000 season. Lee believes the controversy at the final race didn’t help matters either, as most of the competitors were disappointed with the way that management had handled the protest. Ironically, Lee played the role of a peacemaker, and tried to reconcile the differences between the team owners and the series to avoid a split. This culminated in a meeting in a Las Vegas hotel, where Lee presented a “peace offering from the series owner and a new plan for the 2001 AIS season” to the team owners, but the owners weren’t interested. According to Lee, “It was obvious that everyone already had their mind made up. It was decided we were starting a new series and if I wanted to keep racing Indy cars I had to jump on the bandwagon.”

And so there was another “open-wheel split.” The AIS called off the 2001 season and struggled on through 2002 with a couple more events, but the breakaway United States Speedway Series (USSS) featured many of the competitors from the AIS. Lee also became the operations manager for the USSS, and served in that role for three more seasons alongside his racing duties.

Lee drove another three seasons in the USSS for David and Bud Hoffpauir’s Loophole Racing, which had previously entered Dan Drinan to the 1996 Indy 500. “If it was not for David and Bud putting me in good equipment for those three seasons, I could not have pulled it off,” said Lee. “Both David and Bud recently passed away and I can never repay them for what they did for me. They helped a lot of people achieve their dreams, mine included.”

In keeping with the spirit of the AIS, Lee and the USSS would continue to bring Indy cars to various markets across the Southwest. When asked if he had a favorite venue, Lee said, “It is hard to choose a favorite track because I had a lot of fun on most of them. Some of the small ovals like Sandia Motor Speedway, Magic Valley Speedway and San Antonio Speedway were fun because they usually packed the place with fans who were very appreciative to even see Indy cars racing in their smaller communities. If I had to pick one, I would have to choose Pikes Peak International Raceway, because I had a lot of laps there both racing and testing.”

Unfortunately, even going racing in the AIS came at a cost. Without the big salaries and personal sponsorships of his CART and IRL counterparts, Lee would always have to make his living elsewhere. By then, Lee had a full-time career in real estate and was also managing service departments at car dealerships, on top of his racing commitments. This busy schedule finally took its toll on Lee, and he walked away from the USSS at the end of 2003 to focus on his real estate career in Colorado. Meanwhile, the USSS operated its final full season in 2005.

Seen here in Las Vegas during a USSS race, this 1990 Lola had a Menard/Buick V6 with no pop off valve. (Photo: Mike Lee)

Reflections

Today, at age 59, Mike Lee is the CEO of Fast TV Network, which he founded to provide a platform for his reality TV show Speedway Driver (its premise is similar to the driver search program that Lee benefited from many years ago, and features appearances by Al Unser, Jr.). Lee’s company eventually created other shows that showcased car culture, Americana, nostalgia, road trips and small-town America. “We never in our wildest dreams expected to get the viewership we did, but we soon realized we had a tiger by the tail. I am most proud of the fact that we were able to launch on Roku and Amazon Fire TV this past February.” He has plans for more episodes of current shows, as well as new shows and a couple of movies. “Most of the TV shows we have done to date are just things we happen to like. It turns out that a lot of other people like them as well so we have a major responsibility to keep it growing.”

Lee is still a big fan of IndyCar. In fact, he has attended 39 Indy 500s and counting. “It is still a thrill to be there in person at the Indy 500. There is nothing like it in the world in my humble opinion. The competition is so close these days you really have no idea who is going to win on any given day. That's the way it should be.” While he is not a big fan of the aeroscreen, he fully understands the need for it. “If you look back at some of the cars we drove with very little head protection, it makes you thankful to still be alive.”

Lee’s Twitter profile still proudly celebrates his 2000 AIS championship title, and he doesn’t hesitate to give praise to the racer who made it all possible. “Say what you want about him, but Bill Tempero was a diehard racer to the core. He cared deeply about AIS and was proud of it.”

“Bill gave a lot of people, including myself, that never would have been able to fund or secure a drive in the big series, the opportunity to race Indy cars. He put together a set of rules that allowed small or large budgets a way to get their car on track. Nobody in the series pretended that we were anything else but racers who wanted to win. None of us were there for fame and fortune. We were there because we loved it. I really hope at some point there is another series like the AIS so racers can have the fun that we had.”

Like this type of content? Want more?

Submit your email address below so we can email it to you.