Once upon a time...

Photo Credit: IMS Museum

The Gist

He was one of the greatest drivers of the pre-WWII era. After winning numerous races and championships, Rudolf Caracciola had only one dream left: to win the Indy 500. Chasing that dream almost killed him.

Once upon a time: Rudi, the Brickyard and the bird

If you would not know any better, you would have called him one of Hitler’s errand boys. Which would have been completely unfair, seeing as he was an outspoken opponent of the Nazi regime. But as a factory driver employed by the national car industry of 1930s Germany, it was almost impossible to completely avoid National Socialism and its representatives. So in 1937, when he won the Grand Prix of Germany at the Nurburgring, he received a gleaming trophy from the Reichskanzler himself. It was a beautiful piece, with a voluptuous Germanic goddess as a central figure – the problem being that it carried a swastika and, as a detail in the flowing hair of the woman, the double lightning bolts known from those feared SS uniforms.

Above all, Rudolf Caracciola (Rudi for friends) was the Lewis Hamilton of the Thirties. Together with other heroes of the era, such as Tazio Nuvolari, Bernd Rosenmeyer and Hermann Lang, he was the face of European motorsports in those days. The war robbed him of what would probably have been his best years. In 1935, 1937 and 1938 he won what was then called a European championship for Grand Prix cars, in a field full of heavy monsters built by Mercedes, Auto Union, Alfa Romeo and Bugatti. There is no doubt that Caracciola would have been one of the stars in the burgeoning Formula 1 World Championship, which eventually took shape only after the war. Instead, he was stuck at home in Lugano, Switzerland, awaiting the end of the fighting.

The Nazi’s continued to pester him during his forced retirement: in 1942, his salary payments were suspended after he refused to show up for an event that was meant as entertainment for German Wehrmacht soldiers. Furthermore, the powers that be inside Daimler had promised him that he could take the beautiful Mercedes W165, in which he came second in Tripoli in 1939, to his villa in Lugano. However, the civil servants responsible for imports and exports to and from the Third Reich decided otherwise, and stopped the W165 at the border.

Photo credit: Wikipedia

Above: Rudolf Caracciola and Bernd Rosemeyer

Mail from America

In 1946, as the world slowly rose to its feet after six years of destruction and despair, a letter fell on his doormat. The letter contained an invitation from the United States – from Indiana, to be precise. The Indianapolis Motor Speedway, now owned by Tony and Mary Hulman after withering away during the war years, wanted to breathe new life into its annual Indianapolis 500 mile race. But to do so the field needed stars, including European ones. So, the Hulman family reasoned, who better than one of the leading names of the pre-war era? Caracciola had always dreamed of the 500 and was still miffed by the fact that he missed the race in 1938, so naturally he agreed.

His plan was to compete in his beloved W165, which he felt was perfect for the Speedway: it was relatively light, much more agile than the enormous W154 that took him to his 1938 championship title and powered by a 1.5 liter, supercharged V8. In short, it was the ultimate ‘mini Silver Arrow’. But the Swiss authorities proved to be an obstacle. Even though his W165 had eventually arrived in Switzerland in late 1945 after the earlier border issues, it turned out to be near impossible for Rudi to actually take it home. He fell victim to sloppy paperwork, combined with a strong mistrust of a German in post-war Switzerland trying to get his hands on a car without solid proof of ownership.

Nevertheless, after lots of discussions and negotiations he finally took ownership of his W165. The next step was to get the car onto a ship heading for the US, which would depart from a French harbor town. Unfortunately, he ran into that age-old, traditional pastime of the French working man: random strikes that continue for weeks on end. He subsequently looked into air transport as an alternative, but when that also turned out to be impossible, it looked like Caracciola would once again miss out on the 500. He decided to make the trip to Indiana regardless, together with his wife Alice, and packed his racing overalls as well – just to be sure.

That turned out to be the right decision. Once the news of Rudi’s presence in Indianapolis started spreading, it did not take long before he got offered a seat. Joe Thorne, a local millionaire who had driven a number of 500s himself before the war, was unable to compete himself because of a recent motorcycle accident. Would Caracciola maybe want to try and qualify the Thorne Engineering Special in his place, he wondered. The deal was signed only a few days before the race, but on May 28, the last day of qualifying, Rudi was finally ready for his Indianapolis debut.

Rudi Caracciola

“It feels like my head is stuck in a bucket.”

For many rookies, dealing with the Speedway is a monumental job. At first sight, to the untrained eye, it looks like a fast yet simple track with four identical turns, but nothing could be further from the truth. The impressive size of the complex, the tunnel vision that transforms Turn 1 into a narrow alley, the threat of severe injury hanging over any driver that cannot control his or her car: it is no wonder that over the years, many drivers have stumbled at the 2.5 mile Speedway. Nelson Piquet almost killed himself in the early Nineties, while five-time world champion Juan Manuel Fangio never even managed to qualify for the big race. To master the Speedway takes bravery and skill. As Mario Andretti once said: “If everything seems under control, you're not going fast enough.”

Photo credit: Wikipedia

Above: Grid of the 1934 French Grand Prix

But Caracciola, who grew up on the banked curves of the daunting AVUS track outside Berlin and the old oval of Monza in Italy, took to the Speedway like a duck to water. And let’s face it: compared to pre-war races through the streets of Monaco, Pescara and Reims, where a pile of straw bales was seen as sufficient protection for both drivers and spectators, the Speedway was a paragon of safety. What’s more, the Thorne turned out to be a fine machine, providing plenty of power and great handling. Caracciola’s only complaint was that the Speedway officials refused to let him compete while wearing his own helmet.

Although ‘helmet’ was a flattering term: in reality, his head cover consisted of a few pieces of cloth sown together, in combination with a pair of goggles. In Europe this type of head cover was still part and parcel for race car drivers, but Speedway authorities required an actual racing helmet made of solid material. The fact that Caracciola didn’t own one was not an excuse. A British gentleman, also active within the American Automobile Association, helped out and offered Caracciola a helmet that was used during the war by a British tank commander. Rudi commented that it felt “like my head is stuck in a bucket”, but he grudgingly relented and returned to the track with his new head gear. Moments later, that same bucket would save his life.

Whatever it was that caused Caracciola’s serious accident, as he was exiting Turn 2, has remained a mystery to this very day. Was it one of the duck families that have been a familiar sight around the Speedway for many years, and once ruined a practice run by Rick Mears? Was it that symbol of American pride, the eagle? No one knows. But after all these years, the most common and plausible theory is still that the crash was caused by an unidentified, but surely feathered, flying object. Eye witnesses say that while steering onto the back stretch, Caracciola suddenly took his hands of the wheel and sank into the cockpit. The bird presumably guilty of the crash was never found at the scene of the crime, which led to some speculation in a local newspaper that a sniper war veteran with anti-German sentiments had tried to take out Caracciola.

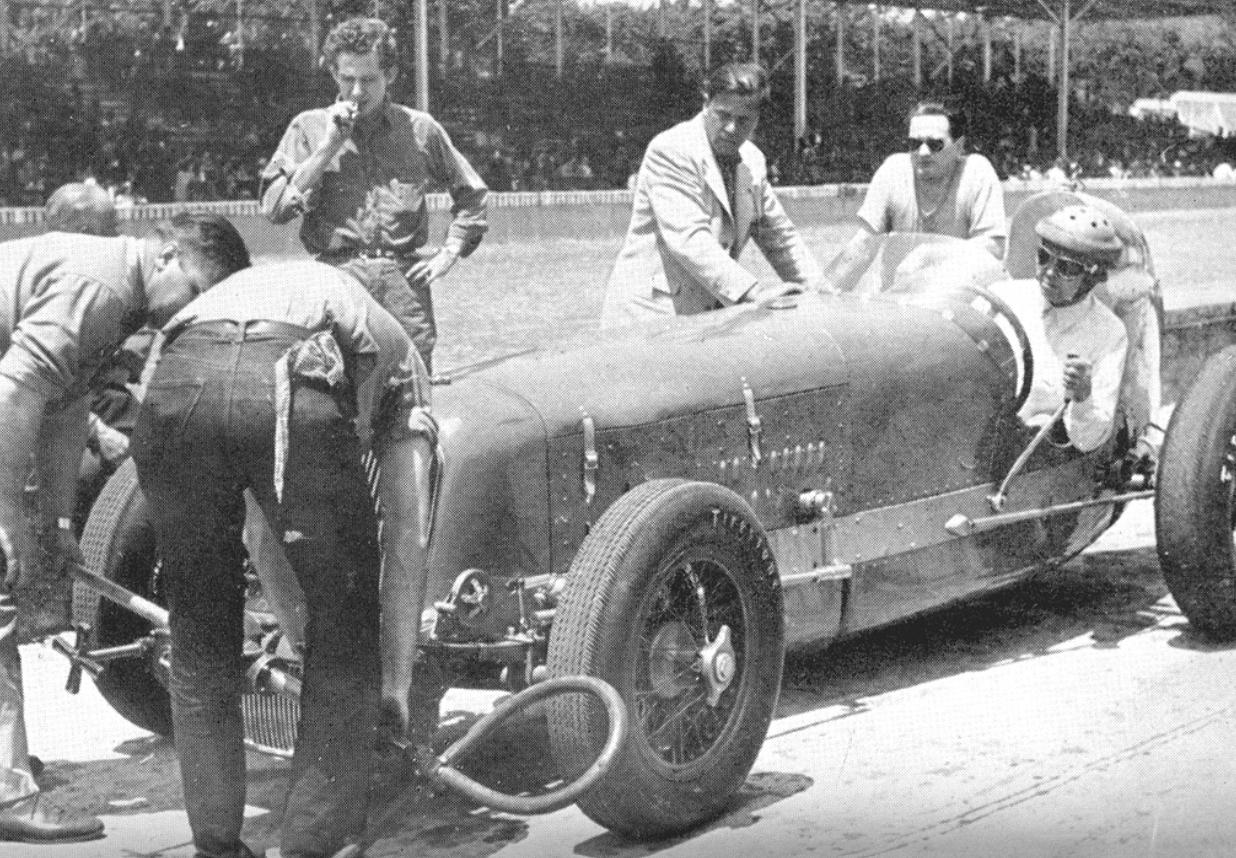

Above: Caracciola in the Thorne Special, incl his special tank helmet

Either way, the Thorne was totalled after the car suddenly veered into the wall surrounding the outside of the track and then flipped over. Caracciola was only a passenger at that point and was thrown out of the car, ending with his head against the asphalt. He was taken to Methodist Hospital in Indianapolis severely injured, where the attending doctors reached a unanimous conclusion: without his borrowed tank helmet, Rudi would have been history.

Photo credit: Wikipedia

Above: The Mercedes W-165

He was in a coma for a week, while his stay at Methodist took at least a month. He never again entered the Speedway as a driver. The performance of his team mate during the race a few days later suggests an intriguing case of what if: George Robson won the first post-war Indianapolis 500 in a second Thorne Engineering Special. But even though he missed out on Indy 500 glory, Caracciola did gain another lasting souvenir from his American adventure: a life-long friendship with the Hulman family. Following his hospitalization, they offered him to stay in their country house as long as he needed to fully recover.

These days, when visiting the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Hall of Fame museum, you can still admire a rich collection of Caracciola’s trophies. Now part of the museum’s permanent exhibition, the collection (including the Nazi symbol-clad trophy from 1937) was given to the museum following the death of Caracciola’s widow Alice, as a token of their long friendship. So while Caracciola never actually raced there, the Speedway remains home to what many consider the most impressive collection of pre-war racing trophies in the world. The only item that is missing?

A stuffed bird.

Santino Ferrucci may be the one holding the off season cards at the moment... where will he end up for 2020?

Like this type of content? Want more?

Submit your email address below so we can email it to you.